Fact Sheet FS714

When is Feed Analysis Necessary?

Before rations can be evaluated or formulated, it is necessary to know the nutrient content of the feeds used. Visual evaluation cannot accurately predict the nutrient value of a feed. Published values for feeds may be used to estimate the general nutrient content of rations (NRC, 2007). However, protein, soluble fiber, and minerals in forages vary with climate, maturity, soil type, and fertilization, and may differ significantly from the average values. Regional averages based on common soil types and growing season may be available from local extension agents or commercial analysis laboratories (for example, Equi-Analytical.com), but even these may be inadequate if dealing with horses with special needs. Forages fed to lactating, pregnant, or growing horses should be analyzed rather than relying on published averages if possible.

Other situations in which feed analyses are recommended include:

- when using non-traditional or commercial mixed feeds for which complete analyses are not available, and

- if suspecting nutritional problems in a horse that would require certain nutrients to be limited.

On farms where hay is purchased at longer than three-month intervals, a sample from each load of hay purchased should be submitted for at least a near-infrared refractometry (NIR) or proximate analysis (See below). If small amounts are purchased frequently, it is not practical to sample each load. In this case, sample every third or fourth lot to get an average for the source being used. For complete information on forage testing, see The National Forage Testing Association (NFTA) website.

How to Sample Feeds

Getting a sample that truly represents the overall feed is not always easy. Techniques differ according to the type of feed sampled and equipment available.

Dry Forages

Ideally, a forage sampler should be used to drill core samples from 10% of the small bales in a batch or lot and at least three cores per bale. These samples should be thoroughly mixed together and a subsample can be taken from there. For a list of where to purchase a hay core sampler, see the Forage Testing website.

If a forage sampler is not available, "grab samples" may be taken by hand, although it will not be as accurate and harder to mix for subsampling. If sampling by hand, latex gloves should be worn, especially if trace minerals are of concern. Contamination from trace minerals on the skin may greatly alter the analyses. Samples should be taken from the inner section of 20 small bales or taken as deeply as possible from 20 sites on large, round bales. If long stem forages are sampled by grab sample, the samples should be chopped to facilitate mixing. Be sure to use stainless steel utensils, as rusty or aluminum implements will potentially contaminate the sample. Mixing is easier if the sample is dried before cutting or grinding, however, the moisture content should be determined if submitting a dried sample for nutrient analysis (See below).

This video is a good tutorial on how to take a forage sample from a bale of hay: Taking a Hay Sample from University of Minnesota (YouTube video).

Figure. Taking a pasture sample on short overgrazed forage.

Pasture Samples

Pasture samples should be taken in a manner that provides a representative picture of the entire field or fields in question. Also, the forage sampled should be from areas and heights that represent a grazing horse. For example, moving in a zig-zag pattern across a large field taking a handful of forage every few steps or obtaining about 20 samples overall and placing them in a bucket. When complete, mix that forage together and fill your sample bag from there. Also clipping the height that horses would graze is ideal, so if the forage is 8 inches tall and the horses are only grazing the top 4-5 inches, that is all that should be removed when sampling. If the forage is short and overgrazed, forage should be clipped down to the lowest level possible. However, make sure to cut longer forages down to about 2 inches once in the bucket and freeze overnight before shipping for the most accurate results.

Grains or Concentrates

Samples (2 to 3 ounces each) should be taken from at least 20 sites and at a variety of depths in binned or bulk feeds. If sacks or bags are used to store the feeds, samples should come from at least two sites from ten bags. Commercially mixed grains that contain supplemental protein and/or mineral in powder form should be sampled only after thorough mixing or from both the top and bottom of the bags to avoid bias due to settling of "fines." The samples should be mixed, and a representative subsample submitted (at least 3 ounces) for analysis. Ideally, the scoop normally used to deliver feed to the animals should be used to obtain the samples.

Selecting a Laboratory

It is important to ascertain if the laboratory to which you are submitting samples is equipped to do the requested analysis. It is also necessary to specify which analyses you want performed, rather than submitting a feed sample with the request to "analyze the nutrient content." Without specific instructions, many laboratories will give either more or less information than is desired. Ask local extension agents or feed stores whether there are feed analysis laboratories in the region. Large feed companies will often perform forage analyses for their clients. Complete listings of certified laboratories are available from the links page of the NFTA's website.

What to Request

The most common nutrient concerns when balancing rations are the water, energy, fiber, protein, calcium, and phosphorus content of the feed. Virtually all feed analysis laboratories are equipped to provide estimates of these in one form or another. Most laboratories also provide analyses of sodium (Na), magnesium (Mg), chloride (Cl), potassium (K), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), manganese (Mn), sulfur (S), and cobalt (Co). Certain trace mineral analyses such as selenium (Se), iodine (I), aluminum (Al), and molybdenum (Mo) require special analytical methods and are not commonly available. Sugars and starches are also commonly analyzed for in feeds and forages, these include different types of sugar analysis Ethanol Soluble Carbohydrates (ESC), Water Soluble Carbohydrates (WSC, which is ESC plus Fructans), and Starch. For an estimate of Non-structural Carbohydrates just add WSC and starch together.

The type of analysis used by the laboratory is important. There are a number of techniques used to determine the nutritional content of feeds, which differ in their accuracy and therefore usefulness. Most laboratories are equipped to do more than one type of analysis. The one(s) employed on a given sample should be selected on the basis of both cost and need for accuracy. Common systems used in commercial laboratories to determine nutrient content are discussed in ascending order of accuracy and cost of obtaining results.

A. Near Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy

Near Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy (NIRS) is based on the assumption that the spectrum of radiation absorbed and emitted by the organic components of feed is similar between feeds of the same chemical and biochemical composition. It is calibrated based on complex mathematical equations and computer prediction models that compare NIRS spectra of feeds to chemical analysis. NIRS is useful in the evaluation and formulation of rations but is of limited value when non-traditional feeds or forages from different regions than those used to calibrate the equipment are used. The technique is more rapid than traditional assays and relatively inexpensive. NIRS reports usually include dry matter, crude protein, acid detergent fiber (ADF), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), total digestible nutrients (TDN), ESC, WSC, starch, non-fiber carbohydrates (NFC), calcium, and phosphorus. However, additional minerals can also be included.

B. "Wet Chemical" Analyses

These laboratory assays involve a variety of chemical and biochemical techniques to accurately measure mineral and biological materials. They are the most accurate (and traditional) methods of analysis.

- Proximate Analysis

In a series of chemical extractions, the crude fiber, crude protein, crude fat (ether extract), and ash (total mineral) content of feeds are determined on either a dry matter or as-fed basis. From these values, the nitrogen-free extract (NFE), which theoretically reflects the soluble carbohydrate content of the feed, is calculated. The total digestible nutrient (TDN) content of the feed is then calculated based on proximate analysis. Until recently it was the standard feed analysis, and virtually all feed analysis laboratories are equipped to perform it.

It is important to note however, that proximate analysis does not measure individual minerals or vitamins. However, it is still useful to obtain a rough, inexpensive estimate of a feed's value. - Detergent Fiber (Van Soest) Analysis

This system is a modification of proximate analysis which uses improved methods for estimating the value of fiber and protein. It has recently been accepted as the standard technique for the analysis of forages for food animals. It uses a series of neutral and acid detergent extraction for analysis of fiber quality. Results of detergent system analysis usually include values for dry matter, soluble carbohydrates, neutral detergent (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), digestible protein, and ash. Many laboratories routinely include it in their "basic" feed analyses. This system also does not estimate individual minerals or vitamins. - "Wet" Mineral Chemistries

Laboratories conducting chemical determination of minerals most commonly use atomic absorption, calorimetric, or spectrophotometric techniques. Some techniques are more adequate for a given mineral than others, but in general, most wet chemistries for the macro minerals are fairly accurate. Problems arise in trace mineral analyses, which are extremely susceptible to errors due to contamination and improper sampling either in the laboratory or at the farm. - Vitamin Assays

Vitamin assays are much less available than mineral assays. Biologic assays, using either animal or bacterial response to extracts of the feed or substance in question, also are used to determine concentrations of most vitamins. These assays are lengthy and expensive. Vitamins that serve as co-enzymes in specific biochemical reactions (ie: niacin, riboflavin, thiamine) may be determined by measuring byproducts of the vitamin-mediated reaction by either calorimetric reactions or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). These assays, however, require a level of sophistication usually found only in research laboratories.

C. Forage Moisture

The quality of hay is determined in large part by the moisture at which it was baled. All commercial laboratories will do determinations of moisture content. It is, however, sometimes advantageous to be able to dry a forage before submitting it for nutrient analysis. If this is done, the moisture content should be determined at the same time. Freeze drying is the most accurate method which results in minimal alterations in the nutrient composition of the feed. If freeze-drying equipment is not available, moisture determination can be performed with a commercially available moisture probe which is used directly on the bales or in the silos or by the microwave technique described below.

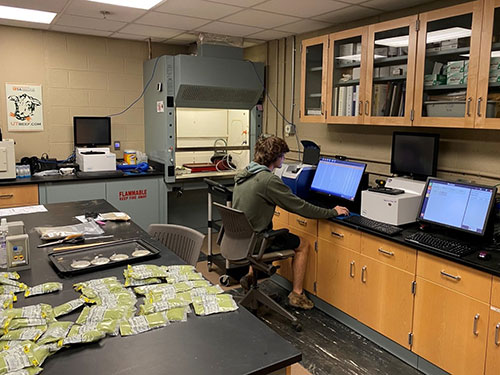

Figure. Forage samples drying in an oven.

Determining the moisture content of forage in a microwave oven requires minimal equipment: a microwave oven, a postal or gram scale for weighing the samples, paper plates, and a glass of water. Weigh a paper plate for each sample to be analyzed and write the weight on the plate. Weigh approximately 3 ounces (100 grams) of chopped forage onto the plate (samples taken by a forage sampler will not have to be chopped). Spread the material evenly over the plate and place it in the microwave. Put a half-full glass of water in the microwave at the same time to reduce the chance of burning the sample. Pasture samples assumed to contain over 50% moisture should be heated at medium heat for four minutes initially. Hay samples (usually less than 30% moisture) should be heated for only three minutes initially. After heating, remove the sample from the oven and weigh it. Stir the forage on the plate and replace it in the oven for another minute. Weigh, stir, and reheat for 30 seconds. Continue drying and weighing until the weight becomes constant. If the sample gets charred, you must redo the analysis on a fresh sample, using shorter drying times. The final weight divided by the original weight multiplied by 100 then subtracted from 100 will give you the percent water in the feed.

Drying in a drying oven is more maintenance-free but could take a few days vs. minutes. Prepare the sample as above and place it in a pre-weighed paper bag or aluminum tray. Place the bag in an oven set to 60 degrees C (about 140 degrees F). Drying time can range from 12-24 hours depending on the initial moisture content. Weigh the dried sample after 24 hours and continue to keep it in the oven for another 24 hours. If the weight remains constant, it has completely dried or continue to try it until weight stabilizes.

Summary

When formulating or evaluating rations, it is necessary to know the nutrient content of the ingredients. While published average values for concentrates may be used, it is strongly recommended that, when economically feasible, forages be submitted for chemical analysis. To sample a feed, at least 20 individual samples should be taken from a variety of sites in the lot, thoroughly mixed and a subsample submitted for nutrient analysis. To insure getting a truly representative sample of hay, it is strongly recommended that a hay corer be used rather than taking "grab samples." If grab samples are taken or samples are mixed by hand, latex gloves should be worn, especially if concerned about trace mineral content. It is important that the type of analyses desired be specified. NIRS is the most rapid and inexpensive analysis. It may be inaccurate, however, if forages from outside of the region or nontraditional feeds are submitted. Proximate analysis provides a reasonable estimate of forage quality but is not as accurate as the newer detergent system of analysis.

References

National Research Council. 2007. Nutrient Requirements of Horses. National Academy Press, Washington, DC.

Photo Credits: C. Williams, Rutgers University; D. McIntosh, Univ. Tennessee; Courtney Heaton, Auburn University; Jaime Hampton, Ohio State Extension; Jason Turner, New Mexico State.

January 2025

Copyright © 2025 Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. All rights reserved.

For more information: njaes.rutgers.edu.

Cooperating Agencies: Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Boards of County Commissioners. Rutgers Cooperative Extension, a unit of the Rutgers New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station, is an equal opportunity program provider and employer.