Fact Sheet FS1320

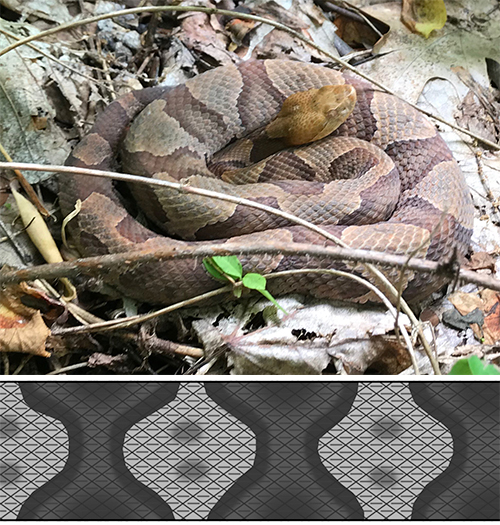

Figure 1. Eastern copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix).

Copperheads are one of just two venomous snake species found in New Jersey. The subspecies that occurs here is the eastern copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix; Figure 1). They are only found in the northern half of the state in parts of the Piedmont, Highlands, and Ridge-and-Valley regions. Most copperhead "sightings" are typically misidentifications of more common species with similar banded patterns. These misidentifications have resulted in several commonly held misunderstandings about copperhead habitat, abundance, behavior, and distribution. Here we provide information on copperhead ecology and important safety information for maintaining positive human-snake interactions.

Distribution and Habitat

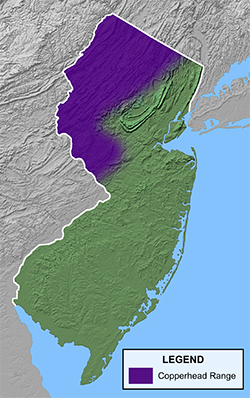

New Jersey’s copperhead populations are patchily distributed within the northern half of the state (Figure 2). They occur only in parts of the Piedmont, Highlands, and Ridge-and-Valley regions, from the Sourlands of Mercer, Somerset, and Hunterdon counties, north to the Delaware Water Gap in Sussex County, and east to the Palisades of Bergen County. Copperhead dens, also called hibernacula, are typically associated with hilly and rocky terrain, but snakes may disperse into surrounding forest, marshes, and fields during the active season. Copperheads are very shy and secretive snakes, preferring to remain concealed within rock, coarse woody debris, leaf litter, or vegetation rather than venturing out into the open.

Identification

Figure 2. Copperhead distribution in New Jersey. Figure by Tyler Christensen.

Adult eastern copperheads typically reach 2–3 feet long. Compared to snakes of similar length, copperheads are very thick and heavy-bodied. They are one of several species in the state with overall brownish coloration and a pattern of alternating light and dark bands or splotches. Various patterns of rings or splotches can be seen in other New Jersey snakes (Figure 3), but the bands found on copperheads are uniquely hourglass-shaped when viewed from above. When viewed from the side, the dark bands are triangular or "Hershey's kiss"-shaped, and the tips of these triangles meet at the snake's back to form the hourglasses. This pattern and coloration help the copperhead blend in astonishingly well against rock and leaf litter. In addition, copperheads have vertical pupils, which in New Jersey is a characteristic shared only with the timber rattlesnake (the state’s other venomous snake). Each of their body scales is also keeled (i.e., has a raised ridge down the center), but that characteristic is not easily seen from a distance.

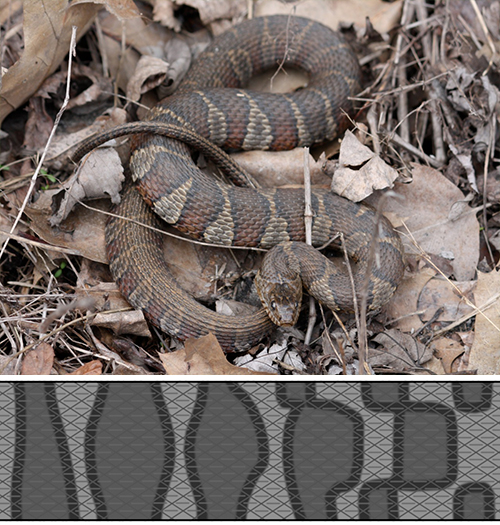

Figure 3. Non-venomous snakes that have a banded or splotched pattern are frequently confused with copperheads, accounting for one of the most common wildlife misidentifications in New Jersey. Snakes most often confused for copperheads are the much more common and non-venomous northern water snake and eastern milk snake. Eastern hognose snakes and immature black racers and black rat snakes may also be confused with copperheads. Northern Water Snake photo courtesy Rebecca Garbo, all other photos courtesy Tyler Christensen.

Status and Conservation

Like all endangered and non-game wildlife species in New Jersey, copperheads are protected by law and are listed as a Species of Special Concern. Consequently, it is illegal to disturb, harass, or harm copperheads or any other species of snakes. Copperheads are declining in New Jersey due to human persecution, road mortality, illegal collecting, and loss of suitable and connected habitats, resulting in their classification as a Species of Special Concern. Habitat alterations also result in barriers to gene flow between populations, which is an increasingly worrisome issue for long-lived species with limited dispersal like the copperheads. Unfortunately, copperheads are frequently killed by people who are concerned for their safety or who simply dislike them or all snakes in general. Because of this, non-venomous snakes misidentified as copperheads are also frequent victims of human persecution.

Life History

Copperheads, like all reptiles, are ectothermic (cold-blooded). However, this does not imply that their body temperatures must match ambient temperatures. Rather, copperheads thermoregulate behaviorally, carefully choosing habitats with a range of thermal conditions and adjusting their positions within those habitats so they can raise and lower their body temperatures, as needed. Consequently, many aspects of copperhead habitat selection and behavior are driven by thermal needs. During a season, copperheads may make repeated visits to preferred basking areas. These are usually sunny clearings, canopy gaps, and forest edges where they can elevate their temperatures and speed up metabolic processes like digestion, ecdysis (shedding), and, in reproductive females, gestation.

Despite being venomous and remarkably well-camouflaged, copperheads are often eaten by predatory birds, like hawks, and by mammals, such as raccoons and foxes. If copperheads manage to avoid predation and negative encounters with humans, they may live 20 years in the wild.

Figure 4. Adult copperhead traveling to its den in late September.

Seasonal Activity

During the brief active season, copperheads must travel from dens to suitable foraging habitats, find and consume enough food to maintain or gain mass, and shed their skins several times per season. Males must locate and court females; females that mated the previous fall must gestate and give birth; and, finally, they must return to their dens before the autumn temperatures drop too low.

Copperheads are active as early as late March. They den beneath the ground in rocky terrain, often with other species of snakes such as garter snakes, black rat snakes, and timber rattlesnakes. They normally disperse from their dens in May, with most traveling to forests, forest clearings, marshes, and meadows to spend the remainder of the active season. Females tend to remain closer to dens in years when they are gravid (carrying young). Periods of travel to and from dens or foraging areas, and courtship during the spring and late summer, are associated with the greatest number of copperhead mortalities (Figure 4). Copperheads typically return to their dens in October.

Figure 5. Recently birthed copperhead neonates.

Reproduction

Courtship and mating typically take place in summer and early fall. Males may be forced to compete with one another for access to receptive females. These interactions consist of physical wrestling matches, where the males attempt to pin one another to the ground. Mated females will not begin to gestate until the following year. In early summer, gravid females will select sunny areas with plenty of shelter—especially rock, vegetation, and woody debris—to complete their gestation. Females typically give birth in August or September. They are viviparous, meaning they bear live young. A typical litter consists of 6–8 neonates but can have as many as 15–20. Neonates are only about the size of a green bean (Figure 5). After giving birth in August or September, females return to their dens thin and underweight. It takes at least a year or two to recuperate enough energy reserves to reproduce again.

Prey and Foraging

Copperheads are highly selective of what they choose to strike and eat. The diets of adult copperheads are comprised of small mammals no larger than mice, voles, and shrews, but they may eat frogs and small birds, on occasion. Juvenile copperheads are fond of insects and other invertebrates.

Like other snakes, copperheads have a keen sense of smell that they use to gather information about their surroundings and locate prey. Snakes flick their forked tongues to gather minute particles from the air and return them to an olfactory receptacle (called the Jacobson's organ) on the roof of their mouths.

Copperheads use their sense of smell to locate areas where their preferred prey is active. They may assume an ambush posture and remain coiled and motionless, sometimes for days, waiting for a suitable prey item to come within striking distance. They may also choose to forage by actively searching and scent-tracking their prey.

Copperheads are one of the pit vipers—the group of snakes that includes the cottonmouths and rattlesnakes—and have heat-sensing organs (or "pits") located on the face between the eyes and nostrils. These heat-sensing pits augment their ability to detect and strike prey once it is in close range, even in low-light conditions.

Human Safety

Despite their undeserved bad reputation, copperheads are docile snakes that do not bite unless provoked. Most bites occur when snakes are being deliberately harassed, handled, or hurt. Though venomous, their venom is not especially potent. Less than 0.0001% of copperhead bites between 1983 and 2010 resulted in death, and no one has ever been killed by a copperhead in New Jersey. Nonetheless, a bite from a copperhead should be treated as a serious injury and medical attention should be sought immediately. If you are hiking in copperhead habitat, take reasonable precautions: wear closed-toed shoes, keep dogs leashed at your side, and remain on marked trails. If you see a snake and suspect it is a copperhead, keep a minimum distance of six feet between you and the snake. If the snake is on a trail and may be encountered by other hikers, you can try gently nudging it along using a long stick. If a copperhead is in a location where you are concerned for either the snake’s safety or your own, call the NJ Venomous Snake Response Team (contact information below).

NJ Venomous Snake Response Team

References

December 2024

Copyright © 2025 Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. All rights reserved.

For more information: njaes.rutgers.edu.

Cooperating Agencies: Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Boards of County Commissioners. Rutgers Cooperative Extension, a unit of the Rutgers New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station, is an equal opportunity program provider and employer.