Fact Sheet FS1281

When most people think of ticks in New Jersey, they usually envision blacklegged ticks (a.k.a. deer ticks, Ixodes scapularis), which transmit Lyme disease bacteria, or American dog ticks (Dermacentor variabilis), often found on canine companions. But for some time, the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) has been a problem in the southern part of the state. And there are indications it may be moving north.

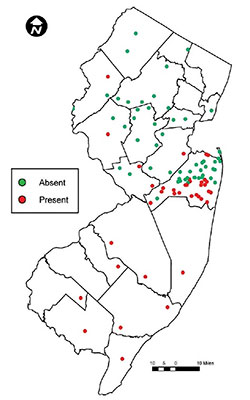

Fig. 1. Documented distribution of lone star ticks in New Jersey, 2008. Reproduced from Schulze et al. (2011)

History and Distribution

The lone star tick was the first tick described in this country in 1754. The Swedish naturalist Pehr Kalm, during a visit to Fort Anne, NY in June 1749, remarked they were so plentiful that "scarcely any one of us sat down but a whole army of them crept upon his clothes" (Kalm 1771, pg. 303). However, possibly due to farming practices that destroyed the forests, and deer hunting that reduced a critical tick host, by the late 1800s lone star tick populations had declined to the point of extinction in many parts of the northeastern U.S. As a result, until about 60 years ago they were mostly restricted to the southeastern U.S., the Gulf coast, Texas, and Oklahoma. Now they are back and expanding.

In New Jersey the lone star tick is found mostly in the southern part of the state (Fig. 1) in xeric forested pine/scrub habitats and along the Atlantic coast. In many areas where it occurs, it is the most abundant tick species, outnumbering blacklegged ticks by a factor of 3:1 or more. Importantly, it is now detected north of Monmouth, the central-coastal county that used to be the upper boundary of its range (Fig. 1).

Life Cycle and Identification

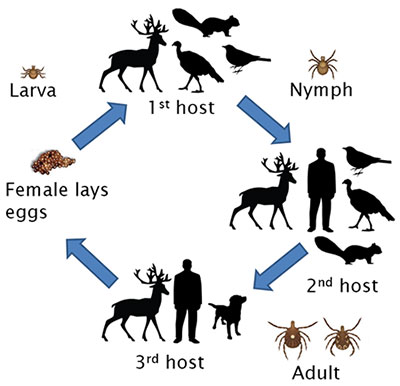

The lone star tick, like blacklegged and American dog ticks, is a hard-bodied tick with four life stages: egg, larva, nymph, and adult (Figs. 2 and 3). Typical of all hard ticks, each active stage feeds only once. Larvae and nymphs take a blood meal in order to grow into the next stage, while adult females must feed on blood to lay eggs. All stages of lone star tick feed on deer, but larvae and nymphs have also been found on small- to medium-sized mammals, passerine birds, and turkeys. In New Jersey, lone star adults are active from April to mid-June; nymphs are active from April to July; and larvae are active from July to Sept. Thus, unlike blacklegged ticks that have stages active even in the fall and dead of winter if it is just warm enough, lone star tick activity is concentrated during spring and summer.

Fig. 2. Top row: Lone star ticks, from left: Adult female, nymph, larva. Note rounded body shape. Bottom row: Blacklegged (deer) tick adult female (left) and American dog tick female (right). Note oblong body shape. Photo Credit: Jim Occi.

The lone star tick female is most recognizable by the large white dot on its back (Fig. 2), which is absent in the males. But all life stages of the lone star tick are distinguishable from blacklegged and dog ticks by their rounder shape, with the other two species appearing more oblong or sesame-seed shaped (Fig. 2).

The behavior of ticks searching for a host is called "questing." Despite the term making it sound like they are embarking on a long journey, most ticks simply crawl up to a high point on vegetation, stretch out their front legs, and wait for a host to walk by and brush against them so they can latch on. Additionally, and somewhat menancingly, lone star ticks can actively pursue hosts following CO2 trails and are aggressive biters. All stages of this relatively large tick bite humans, and since they have significantly longer mouthparts than American dog ticks, which are similarly sized, their bites are deep and usually cause a mild allergic reaction (red, itchy lesion) at the bite site within the first 48 hours after attachment.

Medical Importance

Human Diseases

Besides being a painful nuisance, lone star ticks can also transmit disease-causing organisms to humans. In New Jersey, the most prominent infectious agents transmitted by lone star ticks are the bacteria that cause ehrlichiosis, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, which causes human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) and the milder Ehrlichia ewingii. Symptoms of either ehrlichiosis, like those of many tick-borne bacterial infections, include fever, headache, and muscle pains, though not all who are infected will have symptoms (www.cdc.gov/ehrlichiosis). Development of a rash is less common with HME than with Lyme disease or Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and the rash, if it develops, is variable in location and form, and not distinctive. Ehrlichiosis is usually treated with antibiotics, and while the prognosis is good if caught early, the risk of complications increases if left untreated and it can be fatal, primarily among the very young (children less than 5 years), elderly (more than 70 years), and those with immune deficiencies.

Fig. 3. Lone star tick life cycle.

In 2015 there were 61 cases of HME statewide reported to the New Jersey Department of Health, with most cases reported from southern/coastal counties, consistent with the distribution of lone star ticks: Atlantic (9), and Ocean (9), Burlington (7), Monmouth (6), and Salem (4) (www.state.nj.us/health/cd/statistics/reportable-disease-stats). Cases of ehrlichiosis have been increasing annually, both in New Jersey as well as in the U.S. overall.

A recent study based in Monmouth County, NJ found that cases of ehrlichiosis are likely underreported. The expected rates of occurrence were estimated from the abundance of lone star ticks and the known prevalence of the pathogen in the ticks. The underreporting could be due to the fact that infected people without symptoms or with only mild infections don't seek medical help. However, lack of awareness can also lead to misdiagnosis/confusion with other maladies with similar symptoms such as a summer flu.

In addition to the agent of ehrlichiosis, the lone star tick can carry Rickettsia amblyommatis, a bacteria similar to Rickettsia rickettsii, the agent of Rocky Mountain Fever, as well as Francisella tularensis, the agent of tularemia, and a few other pathogens not known to occur in New Jersey, such as Heartland virus.

Of note, a further danger of being bit by a lone star tick is the development of an allergy to red meat, specifically to the polysaccharide alpha-galactose (abundant in red meat) that is triggered by a component of the lone star tick saliva. Symptoms of red meat allergy occur several hours after ingesting food and include upset stomach, diarrhea, hives, itching, and/or anaphylaxis (sudden weakness; swelling of the throat, lips, and tongue; difficulty breathing; and/or unconsciousness, evidence reviewed in Steinke et al. 2015).

Pet Diseases

Companion animals are also at risk from the lone star tick. The same bacteria that causes ehrlichiosis in humans can also infect dogs. Cats can contract "bobcat fever" from lone star ticks, caused by a protozoan called Cytauxzoon felis. Until now C. felis infection has been observed predominantly in the south only as far north as Maryland, but as lone star ticks and bobcat populations expand north, that may change.

Prevention and Control

Personal Protective Measures

Avoiding lone star ticks is the best prevention against their bites and transmissible pathogens. As with all ticks, when spending time outdoors, do not walk through or sit down in tall vegetation or unmowed grass. When walking through woods and natural areas, stay on roads and trails. Ticks usually crawl upwards once they find a host so it is important to securely tuck pants into socks and shirt into pants so they cannot get under the clothes. The use of repellents containing DEET, picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus (p-Mentane-3,8-diol or PMD) is recommended. Repellents should be sprayed directly on skin (unless using sunscreen, in which case the repellent should be applied after the sunscreen). The insecticide permethrin can be applied to clothing, shoes, and gear, but not on skin. Treated clothes, when combined with a skin repellent, provide the best protection.

Another important step to avoid tick-borne disease is to conduct frequent tick checks. Tick checks should be done after returning from spending time outdoors or as part of an everyday shower routine. Body areas to especially focus on are the scalp, behind the ears, armpits, ankles, and groin. Nymphs and larvae can be quite small, the size of a poppy seed or smaller, and be mistaken with freckles. Strategies for tick removal were compared and reviewed by Stewart et al 1998.

Tick Management

A general integrated tick management approach applicable to private yards includes (1) landscaping to make yards inhospitable to ticks, (2) preventing proliferation of mice and deer, and (3) application of synthetic or plant-derived acaricides. Common landscape management techniques recommended for tick control include keeping grass mowed, removing leaves and brush, deer exclusion, and installation of a wood chip barrier between lawn and woods. However, these methods have yet to be formally tested against lone star ticks.

Chemical control of lone star ticks is best done in the spring when adults first become active, usually around mid-May in New Jersey. Many of the most effective acaricides require a pesticide license to apply, which requires hiring a pest control service. For information on how to hire a Pest Control professional please refer to Rutgers NJAES fact sheet FS018.

Recently some 'over-the-counter' acaricide products that can be purchased and applied without a license, were shown to be effective for almost one month against lone star ticks when applied correctly (refer to Jordan et al. 2017) Some natural products have proven efficacy against lone star ticks (Undecanone, Nootkatone) but commercial formulations are not yet available.

What to Do If You Are Bitten by a Lone Star Tick

When finding an embedded tick it is important to remove it immediately because in general, infected ticks are more likely to pass on disease-causing organisms the longer they feed. Commercial tools that grasp the tick mouthparts are overall superior for the removal of lone star nymphs but tweezers can be equally effective for the removal of adults.

The CDC does not recommend testing individual ticks for disease-causing organisms because (1) a bite from an infected tick does not always result in illness; and (2) a negative result can lead to a false sense of security as other, possibly infected ticks, might have been present too.

Aside from removing the tick immediately, the best plan of action is to carefully watch for symptoms of a tick-borne disease like ehrlichiosis (fever, headache, muscle ache, rash, etc.). If symptoms occur, a visit to a physician is warranted.

Conclusion

Lone star ticks are expanding spatially and increasing in abundance across New Jersey. They are an aggressive and relatively large species likely to raise concern in hikers and gardeners. A bite by a lone star tick may transmit the agent of ehrlichiosis, which the CDC calls a "serious illness that can be fatal if not treated correctly." Avoidance and temporary control of lone star ticks can be achieved but significant gaps exist in our knowledge of this tick's ecology, behavior, and physiology as well as the epidemiology of the pathogens it transmits.

References

- Goddard, J. and A. Varela-Stokes 2009. Role of the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum in human and animal diseases. Veterinary Parasit. 160:1-12.

- Heitman, K. N., Dahlgren, F. S., Drexler, N. A., Massung, R. F. and C. B. Behravesh. 2016. Increasing incidence of ehrlichiosis in the United States: A summary of national surveillance of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia ewingii infections in the United States, 2008-2012. Am J Trop Med Hyg 94(1): 52-60.

- Egizi, A., Fefferman, N. and R. Jordan 2017. Relative risk for ehrlichiosis and Lyme disease in an area where vectors for both are sympatric, New Jersey, USA. Emerg. Infect Dis 23(6):939-945.

- Jordan, R. A., Schulze, T. L., Eisen, L. and M. C. Dolan. 2017. Ability of three general-use pesticides to suppress nymphal Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum. JAMCA 33(1):50-55.

- Kalm, P. 1771. Travels Into North America: Containing Its Natural History, and a circumstantial account of its plantation and agriculture on general (translated into English by J. R. Forster). 352 pp.

- Paddock, C.D. and M. J. Yabsley. 2007. Ecological havoc, the rise of white-tailed deer, and the emergence of Amblyomma americanum-associated zoonoses in the United States. In Wildlife and emerging zoonotic diseases: the biology, circumstances and consequences of cross-species transmission (pp. 289-324). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Polanin, N, Maletta, M, and G. C. Hamilton. 2010. How to hire a household pest control professional. Rutgers NJAES Fact Sheet FS018.

- Schulze, T. L., Jordan, R. A., White, J. C., Roegner V. E. and S. P. Healy. 2011. Geographical distribution and prevalence of selected Borrelia, Ehrlichia and Rickettsia infections in Amblyomma americanum in New Jersey. JAMCA 27(3):236-244.

- Schulze, T. L., Jordan, R. A., Healy, S. P., Roegner, V. E., Meddis, M., Jahn, M. B. and D. L. Guthrie. 2006. Relative abundance and prevalence of selected Borrelia infections in Ixodes scapularis and Amblyomma americanum from publicly owned lands in Monmouth County, NJ. J Med Ent 43(6): 1269-1275.

- Sherrill, M. and L. Cohn. 2015. Cytauxzoonosis: Diagnosis and treatment of an emerging disease. J. of Feline Med and Surg 17:940-948.

- Steinke, J. W., Platts-Mills, A. E. and S. P. Commins. 2015. The alpha gal story: Lessons learned from connecting the dots. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 135(3): 589–597.

- Stafford, K. C. 2007. Tick Management Handbook: An integrated guide for homeowners, pest control operators, and public health officials for the prevention of tick-associated disease (revised edition). The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, Bulletin No. 1010.

- Stewart Jr, R. L., Burgdorfer W. and G. R. Needham. 1998. Evaluation of three commercial tick removal tools. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 9:137-142.

February 2018

Copyright © 2024 Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. All rights reserved.

For more information: njaes.rutgers.edu.

Cooperating Agencies: Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Boards of County Commissioners. Rutgers Cooperative Extension, a unit of the Rutgers New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station, is an equal opportunity program provider and employer.